After Thomas Eric Duncan inadvertently brought the Ebola infection to the US, CDC director Thomas Frieden confidently announced, “I have no doubt that we’ll stop this in its tracks.” Two weeks later, after a nurse caring for Duncan contracted the disease, Frieden acknowledged that the CDC needed to rethink its approach to infection control.

After Thomas Eric Duncan inadvertently brought the Ebola infection to the US, CDC director Thomas Frieden confidently announced, “I have no doubt that we’ll stop this in its tracks.” Two weeks later, after a nurse caring for Duncan contracted the disease, Frieden acknowledged that the CDC needed to rethink its approach to infection control.

Flip-flopping by a public official in the face of a high-stakes issue is nothing new, and we shouldn’t be too tough on Dr. Frieden. All eyes are on him and his agency, the CDC has less authority than many people believe, and although the disease is tough to spread it’s deadly… and therefore scary.

Instead, there’s a much bigger challenge that the CDC faces in dealing with the public and its response to Ebola: Edward Snowden.

The connection between the NSA leaker and the CDC’s Ebola headaches might seem tenuous, but it’s real and it’s important. In the wake of Snowden’s revelations about the NSA’s secret surveillance of a huge swath of the American population, skepticism about the government has skyrocketed.

The 2014 Edelman Trust Index, for example, showed trust in the US government dropped 16 points (from 53% in 2013 to 37% in 2014). Similarly, a HuffPost / YouGov poll from March showed that although Americans are split on whether Snowden should be prosecuted, more people than not believe that the public had a right to know about the secret programs.

Couple Americans’ bubbling skepticism with easy access to information (and misinformation) and the challenge grows even bigger. Understanding and dealing with this sea change is critical for the CDC and its advocates.

Here’s an example. The most recent press release from the CDC confidently asserts that, “Twenty-one days is the longest time it can take from the time a person is infected with Ebola until that person has symptoms of Ebola.”

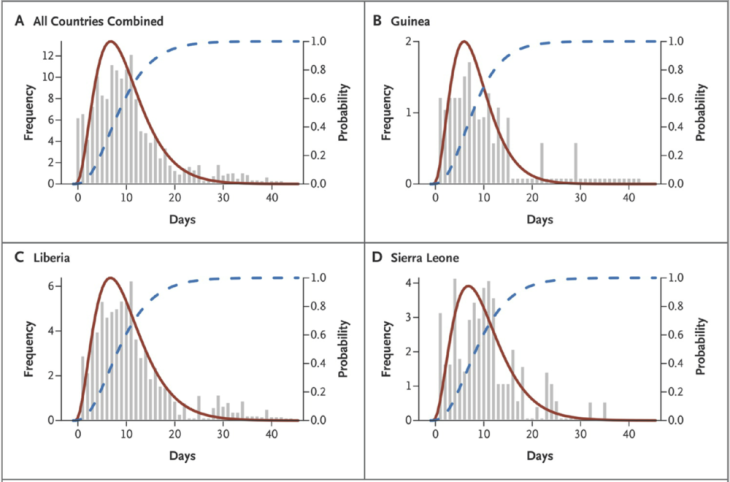

But a recent paper authored by the WHO in the New England Journal of Medicine concludes that about 5% of people who are infected with the Ebola virus take longer than 21 days to exhibit symptoms. That is, of every 20 people infected, on average one will show symptoms after 21 days. Another study estimates that between 0.2% to 12% of people infected with Ebola will have an incubation period greater than 21 days. Thus, the longest time it can take from infection to symptoms is longer than the 21 days asserted in the CDC press release.

This isn’t to say that a cutoff of 21 days is too short. Any policy regarding monitoring suspected cases needs a cutoff, and at 21 days the balance between public health gains and costs to those being monitored might be just right.

This isn’t to say that a cutoff of 21 days is too short. Any policy regarding monitoring suspected cases needs a cutoff, and at 21 days the balance between public health gains and costs to those being monitored might be just right.

The point is that Americans are less likely than ever to believe blanket statements of certainty. All it takes to pressure test such authoritative assertions is a computer, an internet connection, and enough interest to take the time to look. And if a gap is found between the evidence and what someone is telling the public, it’s public trust that takes it on the chin.

The states of New York and New Jersey recently decided to implement 21-day mandatory quarantines of people returning to the US after caring for Ebola patients in West Africa. These policies are likely to be an overreaction, offering only a small (perhaps even hypothetical) reduction in infection risk to the public at the cost of locking up good-hearted and courageous people who risk their lives to care for Ebola patients. Indeed, Governor Cuomo adjusted New York’s policy to allow these workers to be quarantined at home, and Governor Christie clarified that home quarantine was acceptable in New Jersey.

The White House and the CDC argue that this still goes too far, and advocates fervently agree. Indeed, Kent Sepkowitz at the Daily Beast offered a scathing assessment of the policy, even after these adjustments:

“But the adjustment fails to undo the basic badness of the idea—the plopping of a heavy-handed, ineffective, fear-enhancing new dictate right into the middle of a public health emergency that is being handled just fine, thank you, by the people trained to handle it.”

Paradoxically, this sort of “we’re the experts, we’ve got this” positioning will have exactly the opposite effect on many Americans. We live in a post-Snowden world in which people are skeptical of authority and doubly skeptical when we’re told that we should sit back and trust “the people trained to handle it” – even if we should.

So what should the CDC, policymakers and its advocates do? It would be far better to explain the evidence at hand and the process by which a recommended policy was reached. Not everyone will agree with the evidence. Not everyone will agree with how benefits and harms were balanced. But at least we will understand how the policymakers came to their conclusions, and reach agreement on where we disagree.

SOURCES

- Muskal, M. Four Ebola quotes that may come back to haunt CDC’s Tom Frieden. Los Angeles Times (2014).

- Weaver, D. Timeline: The struggle to stop Ebola. TheHill (2014).

- 2014 Edelman Trust Barometer. Edelman.

- Swanson, E. Americans Might Not Support Edward Snowden, But They Support Disclosing Programs. Huffington Post (2014)

- CDC Announces Active Post-Arrival Monitoring for Travelers from Impacted Countries.Oct 22, 2014.

- Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa — The First 9 Months of the Epidemic and Forward Projections. New England Journal of Medicine 371, 1481–1495 (2014).

- Haas CN. On the Quarantine Period for Ebola Virus. PLOS Currents Outbreaks. 2014 Oct 14.

- Sepkowitz, K. New York & New Jersey’s Ebola Quarantines Are an Insane Overreaction. The Daily Beast (2014).