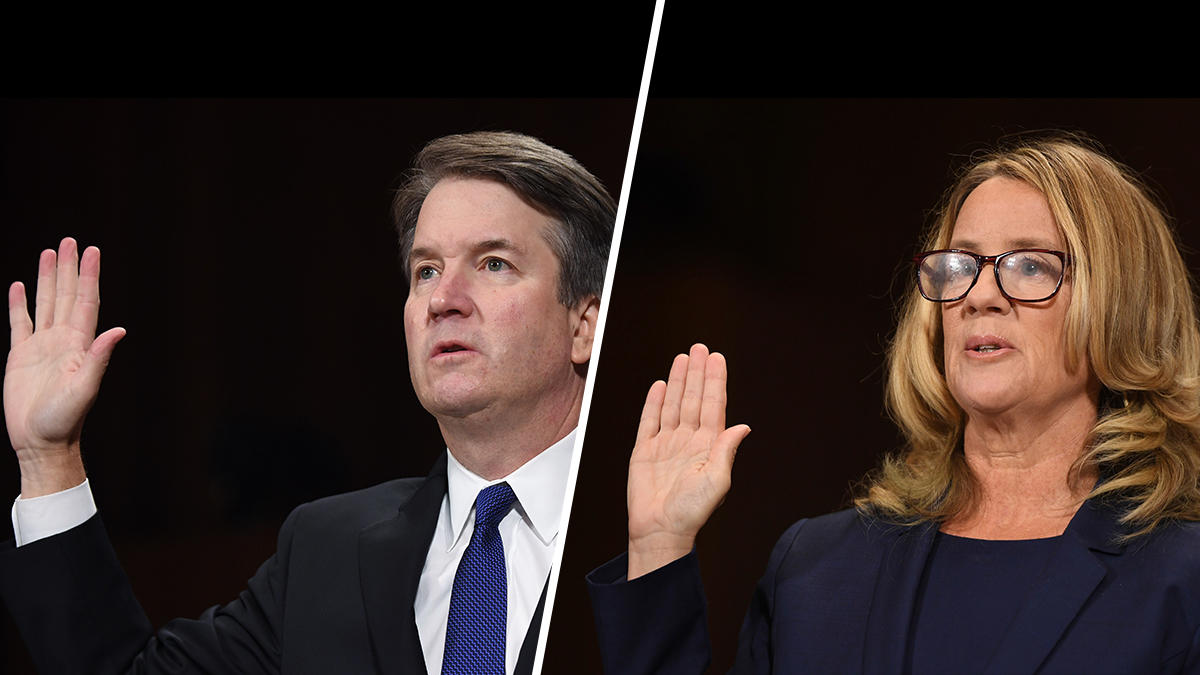

We will never know for sure whether Judge Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. But there is a way that can help us all think a bit more rationally when it comes to deciding how to proceed, and to surface the sources of our disagreements.

We will never know for sure whether Judge Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. But there is a way that can help us all think a bit more rationally when it comes to deciding how to proceed, and to surface the sources of our disagreements.

Let’s with a couple of things on which we’d probably all agree: if we knew for certain that Kavanaugh sexually assaulted Ford (or anyone else), his appointment to SCOTUS should be denied. On the other hand, if we knew for certain that no such assault occurred, then his nomination should move forward to a full vote of the Senate.

Of course, at this point we can’t be completely certain either way. We can, however, engage in a thought experiment to help us think more clearly about what to do next.

Suppose that the probability that Kavanaugh committed sexual assault is p. Right now, all we know is that p is greater than zero and less than one. But here’s the thing: it turns out that we don’t need to know the exact value of p to know what to do next.

There’s one critical question we all need to answer: what’s the maximum value of p for which we are comfortable moving ahead to a full vote instead of running a thorough investigation of Dr. Ford’s claims? If p is anything below that value, we should allow Kavanaugh’s nomination to proceed; if p is greater than that value, we should put things on hold and investigate.

This threshold value of p – call it the breakpoint probability – should reflect the balance of many factors. Some of these factors cause the breakpoint to rise: the cost of delaying the vote on an innocent nominee, the potential that sexual assault claims will be used by the opposition to gum up the nomination process in the future, the wear and tear of the process on an innocent nominee and his or her family, and the like.

Other factors cause the breakpoint to drop: the cost of appointing a person with a history of sexual assault to the SCOTUS, the difficulty of removing a bad justice once appointed, and the chilling effect that moving ahead without an investigation will have on victims of sexual assault coming forward in the future, the wear and tear on a victim of sexual assault whose claims are dismissed by our nation’s leaders, and the like.

For me, the breakpoint probability is very low. Delaying the vote for an investigation comes at very little cost in terms of whether we will wind up with a competent nominee. But more importantly, proceeding as if Dr. Ford is not to be believed incurs a far greater cost to our culture and country than does the risk that such claims will be used to sidetrack future nominations. I think even a 1% chance that Kavanaugh committed assault is too high to warrant skipping an investigation, and the sum total of the testimonies of Dr. Ford and Judge Kavanaugh put the probability well above that breakpoint.

But that’s just me. Each of us will probably weigh these factors differently. The important thing at this point is for us to stop speaking in certainties, as this is neither useful nor necessary. Instead, let’s each think about what our breakpoint probability is, and whether the current state of information puts us above or below that value.

This approach will also allow us to smoke out the reasons we disagree: do our breakpoint probabilities differ? If so, why? Or do we roughly agree on the breakpoint probability but disagree on where the current state of information puts the probability relative to that breakpoint?

In my experience, identifying the specifics around where we disagree almost always identifies areas in which we agree, and issues or factors that we may have overlooked or failed to fully appreciate. I urge you to give it a try. You may be surprised about how it changes the nature of the discussions we all need to have.